How Venice gets drinking water surrounded by salty, brackish water.

Venice was one of Europe's biggest cities. Initially its drinking water was served by a series of almost 6,000 cisterns built to capture rainwater. Today an aqueduct brings fresh water.

Managing Drinking Water in Venice: The Cistern-System from the 12th Century to Today

Much of this copy is copyright: David Gentilcore, PI of the ERC advanced grant "The Water Cultures of Italy, 1500-1800", Ca' Foscari University Venice / The Global Network of Water Museums (WAMU-NET).

Venice is a peculiar city: it floats on water but doesn’t have drinking water. So, citizens had to invent new systems to gather and store drinking water, such as the well-head, still visible in the city center.

How Venice received fresh water.

The entire saltwater lagoon where the unique city of Venice stands had through the centuries one major problem: how to obtain fresh water? As the city’s chronicler Marin Sanudo wrote (1490): “Everything abounds except fresh water, at any time, such that Venice is in water and yet has no water”. This was the situation in what was then one of Europe’s largest cities.

Underground rainwater cistern — seen in squares throughout the city.

The solution was a dense network of underground rainwater cisterns - eventually numbering close to 6,000 - located under squares and courtyards, buildings and streets.

Venice’s famous ‘wells’, with their characteristic ornate well-heads, were actually complex devices for capturing, filtering and storing rainwater underground. Nowhere in Europe was the approach to rainwater capture so systematic and widespread, the city concerned so populous, the technology so sophisticated, and the management so carefully regulated as in Venice.

By the 16th century much of Venice’s open space - its squares and streets - was dedicated to water capture in order to supply these cisterns. As the city’s population increased, new cisterns were built to meet the growing demand, both public and private. An innovation was to use rooftops, equipped with stone guttering, to capture rainwater and channel it down to cisterns located underneath the buildings themselves. Venice itself had become a sophisticated machine for capturing and storing rainwater in its small islands.

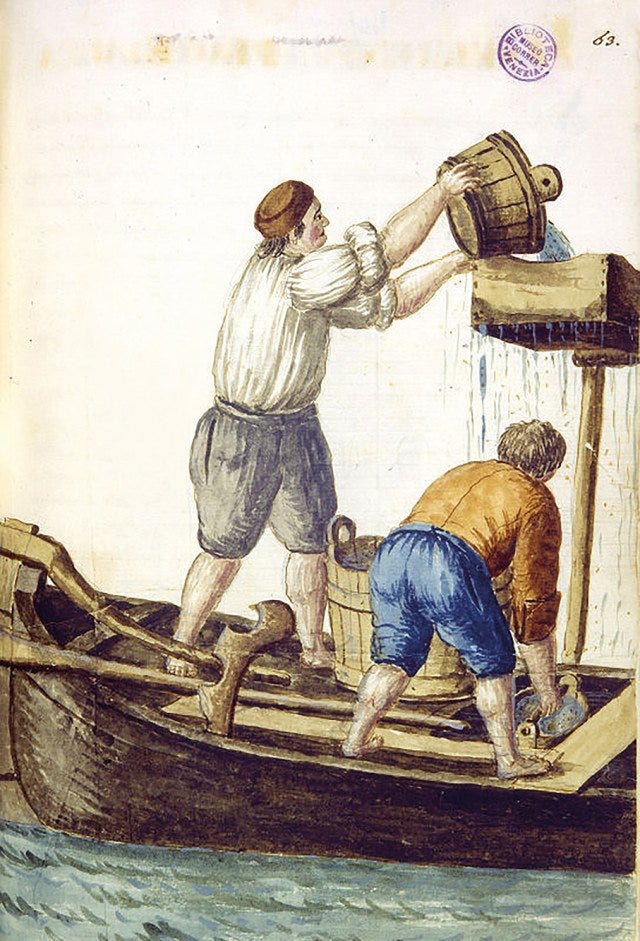

‘Watermen’, known as acquaroli, were put in charge for bringing in supplies of fresh water. They were controlled by the government.

Because Venice’s supply of rainwater was not always sufficient, from the Renaissance period the ‘watermen’, known as acquaroli, were put in charge for bringing in supplies of fresh water. Using special flat-bottomed canal barges known as burchi, the Venetian watermen would take on water from the River Brenta and transport it across the lagoon. On arrival, the watermen employed a series of wooden implements to pour the water into individual cisterns.

The physician and Venetian resident Tommaso Rangoni (1577) described the waters as “agreeable, without taste and colour, indeed sweet and limpid and light”.

The volume of water provided by the cistern-system in 1500 has been calculated at a potential 6 litres per person per day and in 1800 a Venetian engineer calculated the amount then available as 10.7 litres. This is a reasonable amount by early modern standards - compared to Paris’s 4 litres - if somewhat low by today’s baseline standards. World Health Organization guidelines suggest that 7.5 litres a day per person is sufficient for hydration and incorporation into food (a figure which should be doubled to include basic hygiene needs). Through the time, Venice’s cisterns had an estimated total capacity of 450,000 cubic metres.

Functionality: Past, Present and Future

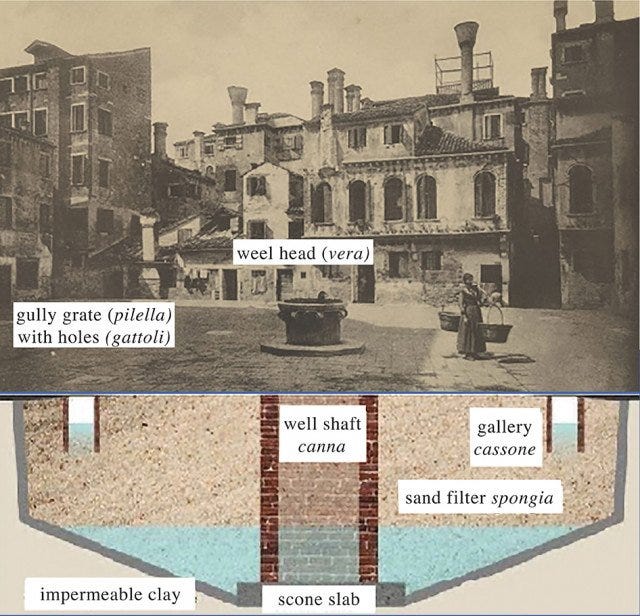

The Venetian-style ‘well’ was typically located in the middle of a public square or private courtyard. On the surface only the marble or brick well-head would be visible, providing support for those drawing water as well as a decorative element.

Surrounding the well-head was the broad stone-paved area of the square, sloping down slightly on all sides from the well-head and interspersed with gully grates made of stone, pierced with holes through which the surface water would drain. It would then collect in underground galleries or tanks made of brick.

The Venetian cistern system.

The actual cistern-system occupied most of the vast area underneath each square. It consisted of a large broad basin, round or four-sided, dug to a depth of 3-4 metres below the normal high-tide level and filled with sand. From the galleries, the water would then filter through the sand, as if in imitation of a natural water table.

The cistern’s walls and floor were lined with a layer of impermeable clay half a metre thick to prevent the rainwater from flowing away (and saltwater from flowing in). Located in the centre of the cistern was the well-shaft, built of special bricks and water-permeable mortar, into which the water would accumulate. The well-head sat on top of the shaft, allowing access to the water below.

The water system had limitations

There were two serious limitations to Venice’s cistern-system, both caused by water—too much and too little. Too much, in the form of Venice’s notorious high tides, would flood the cisterns with salt water and waste. Too little, in the form of periods of drought, not only meant no water; the insides would crack and brackish water would pour in. Either eventuality would have made them unusable, necessitating constant supervision and maintenance.

Despite these limitations, Venice’s cistern-system continued to impress visitors and engineers alike throughout the 19th century. The French scientist and author Louis Figuier referred to it as proof of the saying that “necessity is the mother of invention” in his survey of “the marvels of industry” (1875).

The construction of Venice’s aqueduct in 1884, brought fresh water to the city from the mainland.

In 1884, after many years of discussions, projects, and modifications, a public aqueduct was inaugurated, one which took water from an aquifer about 30 km. from the city.

The entire cistern-system was slowly decommissioned. Wells are now strictly ornamental, with rainwater diverted into the city’s canals.