Relearning history at Valley Forge

I realized I must have been sleeping or not paying attention when the Valley Forge, part of the Revolutionary War, was covered in whatever grade we studied it.

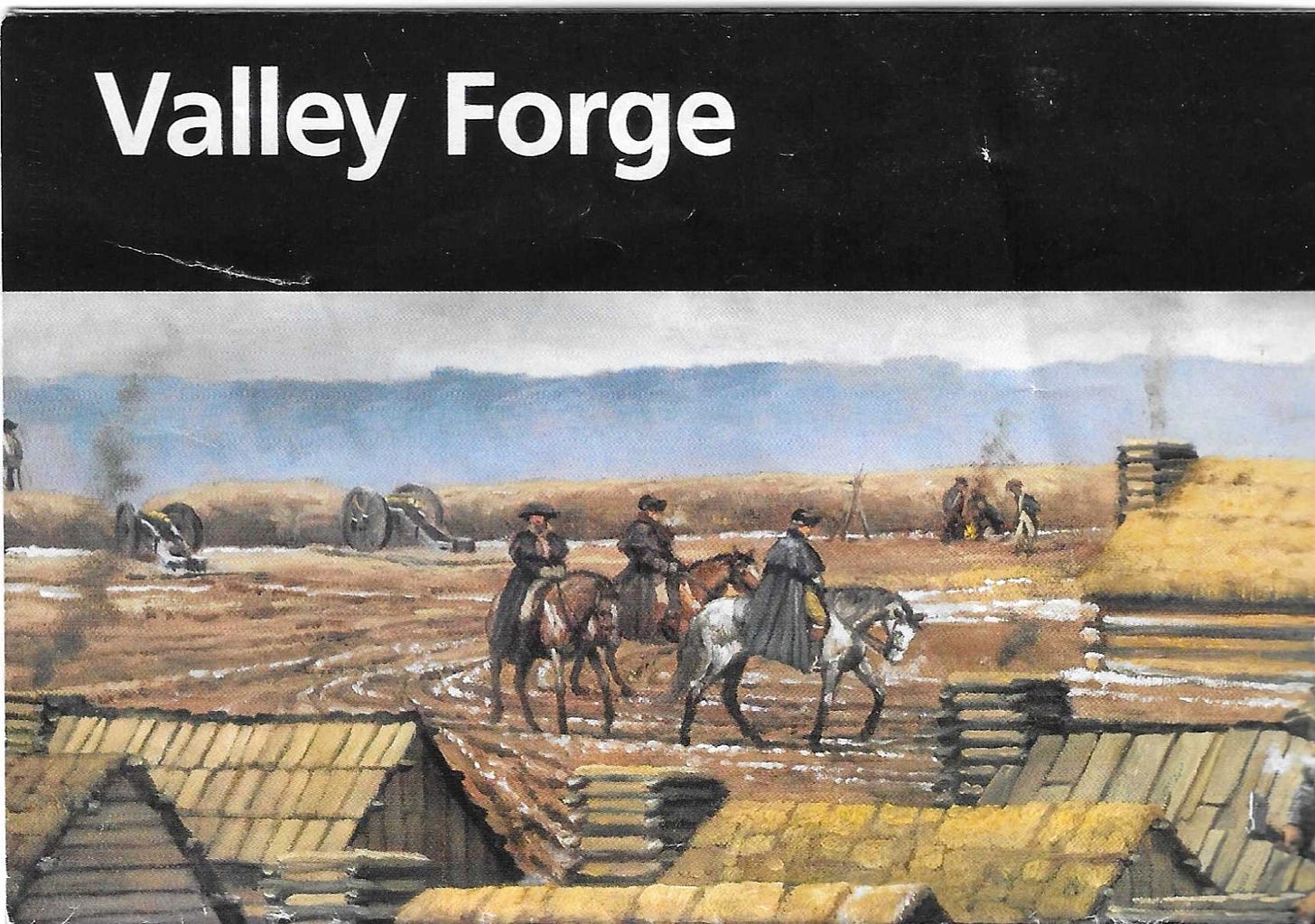

After a recent visit to the Valley Forge Historical National Park near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, I returned with a far different picture of the famed winter encampment.

My image of a ragtag group of men barely surviving a miserable winter in a cold, muddy valley encampment was incorrect. Others I talked to thought they fought there, but they didn’t.

I knew General George Washington had most of the Continental Army encamped at Valley Forge over one winter, but I didn’t know why. And I certainly didn’t know that it changed the war's course.

My visit to Valley Forge with park rangers, a video, and a tour was a real education about that winter during the Revolutionary War.

A trip to the Valley Forge Visitor Center, talking with the friendly and knowledgeable rangers, watching the informative short film about the encampment, and then driving to the nine stops along their downloadable tour certainly reeducated me.

Well, maybe just a little of my understanding was correct. It seems many men wore ragged clothing, and a few even had no shoes, but others had full uniforms. I also learned that calling them an army when they first encamped there was stretching it as they were made up of separate militias from and loyal to their specific states.

And, while it’s called Valley Forge (as there was once a forge down by the Schuylkill River that the British had destroyed), they encamped on a ridge! Yes, the highest ridge around with a commanding view of the surrounding hills and valleys and, I assume, of any army that might want to approach or attack. Good move, George!

Valley Forge was a perfect war encampment — defensible and not too far from Philadelphia.

Just before the winter of 1777, the British had taken Philadelphia, our fledgling country’s capital. General Washington wanted to be close enough (18 miles) to restrict them from taking more territory while also being far enough away that the British couldn’t quickly attack them. As it says on the Valley Forge website: “As he chose a site, Washington had to balance the congressional wish for a winter campaign to dislodge the British from the capital against the needs of his weary and poorly supplied army.”

“Poorly supplied” are the operative words for the encampment that included nearly 12,000 “soldiers” plus at least 400 women (wives of enlisted men and a few generals) and children of various ages. As it says in the National Parks’ write-up online: “While most were of English descent, African, American Indian, Austrian, Dutch, French, Germanic, Irish, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Prussian, Scottish, Spanish, and Swedish persons also filled out the ranks.” Yes, it was interesting to learn that African Americans, both free and enslaved (their “masters” sent them instead of fighting themselves), fought for the Continental Army.

But even more interesting was how this diverse group was transformed into a disciplined and effective army. Yes, they had to work together to build the many log cabins needed for their housing and to dig the trenches for their defenses if the British might attack (which they didn’t). But it was a former Prussian officer, Baron Friedrich von Steuben, who Washington brought in to train and make the troops into one army.

His quote about how he dealt with the soldiers certainly shows the difference between the Old Country and the New: “You say to your soldier [in Europe], ‘Do this’ and he doeth it, but [at Valley Forge] I am obliged to say, ‘This is the reason why you ought to do that,’ and then he does it.”

On the day we visited, joggers and walkers took advantage of the 35 miles of trails in the park. While all was interesting on the 10-mile encampment tour, the things that stood out to me were state monuments along the way, the rebuilt log cabins for the soldiers, the National Memorial Arch, which was dedicated in 1917, and the beautifully preserved yet surprisingly small stone home that was Washington’s Headquarters.

The Memorial Arch — Determination to persevere

The map we followed notes that the words “We were determined to persevere” were written by Private Joseph Plumb Martin in his journal, and it was that determination that the Memorial Arch celebrates. Considering that the biggest problem at Valley Forge was feeding and clothing the vast “army” of people, perseverance was an admirable quality.

Recognizing and remembering the sacrifices made by these soldiers (and the local farmers who stepped up to help supply them) might help many today to remember the principles our country is based upon and how hard they fought for. One of the inscriptions on the arch partially reads, “And here in this place of sacrifice … out of which the life of America rose to regenerate and free, let us believe with an abiding faith that to them union will seem as dear and liberty as sweet and progress as glorious as they were to our fathers …”

The United States seal celebrates the result of the six months at Valley Forge – Out of Many, One (E Pluribus Unum) – as Washington and his generals could shift soldiers’ allegiance from their home states to the United States. It was at Valley Forge where they became an actual army as they spent months training to fight as one unit with the same tactics.

The Revolutionary War lasted another five years. However, Britain faced a unified army.

the park’s information says, “The Continental Army departed camp as a unified army capable of defeating the British and winning American independence … Valley Forge was a key turning point.”

Much as I feel everyone should visit the Civil War battleground at Gettysburg to appreciate the sheer magnitude of the horrors of that war, so do I hope that more people visit Valley Forge Historical National Park to learn more about the many sacrifices made so that our country could come together for its freedom.